Virtual Reality: What is it? How does it work? Why should you care?

15th August 2016 by Sarah Mohamad

What is virtual reality? Virtual reality (VR) is about making an imaginary environment feel very real - real enough to fully immerse you in a simulated world. VR is achieved using a head-mounted display (HMD). VR simulations can include visual, tactile, auditory and sometimes even olfactory experiences – you could be fully immersed in a virtual Tuscan garden in the summer, with the wind in your hair, and the smell of jasmine and freshly-cut grass around you. Lifelike virtual experiences can be enhanced by using omnidirectional treadmills to allow free 360 movement; wired gloves can provide haptic feedback – you could be physically walking around your virtual environment in any direction without bumping into your coffee table; you could even hover your fingers near a virtual fireplace and feel the heat. How does virtual reality work? Virtual reality headsets or head-mounted displays (HMDs) are made of two video feeds sent to the screen within the HMD, powered by a device or computer

What is virtual reality? Virtual reality (VR) is about making an imaginary environment feel very real - real enough to fully immerse you in a simulated world. VR is achieved using a head-mounted display (HMD). VR simulations can include visual, tactile, auditory and sometimes even olfactory experiences – you could be fully immersed in a virtual Tuscan garden in the summer, with the wind in your hair, and the smell of jasmine and freshly-cut grass around you. Lifelike virtual experiences can be enhanced by using omnidirectional treadmills to allow free 360 movement; wired gloves can provide haptic feedback – you could be physically walking around your virtual environment in any direction without bumping into your coffee table; you could even hover your fingers near a virtual fireplace and feel the heat. How does virtual reality work? Virtual reality headsets or head-mounted displays (HMDs) are made of two video feeds sent to the screen within the HMD, powered by a device or computer

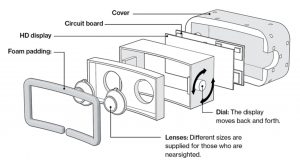

- Lenses are placed over the display to focus and reshape the picture for each eye

- The video feed provides a slightly different video angle in front of each eye. This is needed to create a stereoscopic 3D image.

- The speed of video frames (frame rate) required for VR is higher than that required for normal TV/movie viewing, at a frame rate of between 60 and 120. This makes the experience realistic and immersive; it also avoids causing simulation sickness (similar to travel sickness).

Oculus Rift Schematic[/caption]

Oculus Rift Schematic[/caption] - The HMD is usually capable of head-tracking. This increases the immersive experience by making the simulated environment move with your head movement – when you look down, you can see the virtual ground; when you look up you can see the virtual sky.

- Head-tracking is achieved using sensors inside the HMD; these include a gyroscope (measures rotation), accelerometer (measures acceleration) and a magnetometer (measures magnetic field).

- Positional-tracking can also be included in the VR hardware set-up to increase the realism of the VR simulation. It is usually made of an external motion tracking sensor that detects the precise position of your head. Unlike head-tracking, positional tracking allows you to move around within the 3D space – it detects all directions of movement (i.e. if head tracking allows you to look down and see the ground, positional tracking allows you to bend down and look at the ground up-close. Details, like tiny ants, become visible).

- In the very near future, eye tracking capabilities will be incorporated into the HMD. This will increase immersion by allowing your virtual environment to react to where you are looking within the virtual space (e.g. catching the eye of a virtual person, could make them to look back at you or even interact with you).

Virtual reality is an entirely different medium with thousands of life-changing possibilities. In Chris Milk’s heart-warming TED talk, The Birth of Virtual Reality as an Artform, the impact of VR on storytelling is dramatically demonstrated using an easily made HMD.

At medDigital, we took a dive into the many fields that VR could revolutionise: Education, journalism, gaming, therapy, art, and a dozen other concepts and applications. With a pinch of creative license, we’ve described some of these experiences through the eyes of medDigital’s Victor, Steph, and Matt.

In the RCSi Medical Training Simulator, Victor turned up for his shift at the emergency room. The general surgeon, anaesthetist, and the rest of the team were already there, towering over a car crash victim. Victor was in scrubs, ready for surgery. “Which is the location for the chest drain insertion site?” they asked him. He looked more baffled than usual. A while later, we asked Victor how the surgery was going. "I've lost this patient 3 times..." "oh no. Four now."

Meanwhile, inside a US prison, Steph was thrown into solitary; 23 hours a day in a 6x9 cell was her life for a month, a year or perhaps more. What felt like peace and quiet at first, quickly became deadly silence. For company, she had a toilet, a bed, the shouts of prison guards, the sinister laughter of other prisoners, and the rhythmic banging of a dinner tray. She lost track of time. Days were marked by cold meals appearing and disappearing, hallucinations of enemies in her cell. Steph didn’t last in The Guardian’s 6x9: A Virtual Experience of Solitary Confinement.

Although that was the virtual end for Steph and Vic, Matt may have discovered a new career path (EVE:Gunjack)… Matt's first day as gun-turret-operator in the depths of space was promising. He dodged a barrage of enemy space-fire like a seasoned Trekkie, gracefully timing his reloads between enemy shots. It was all going so well, until he crashed into his own missile.

Next time, we’ll take you on a deeper dive of the 10 useful ways you can use virtual reality right now.